Streets of Renewal: Envisioning a Traffic Plan for a Safer French Quarter

Introduction

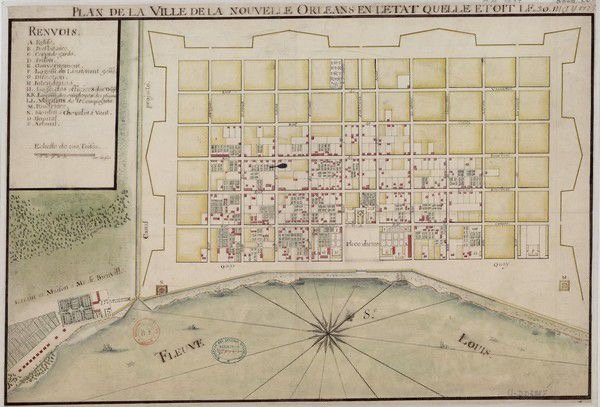

A 1725 map of New Orleans shows Adrien de Pauger's original street grid, which is still evident in today's French Quarter. (National Library of France)

Under the leadership of our first colonial governor, French engineer Adrien de Pauger planned the street grid of the French Quarter in 1721…roughly 164 years before the use of the internal combustion engine on it’s public thoroughfares. As evidenced by the carriage ways in some French Quarter residences, the first four wheel vehicle in the historical district was drawn by mules. Slow and cumbersome, the carriage was a vehicle of privilege.

In the 1700’s, carriages were generally considered a luxury item only accessible to the wealthy, meaning common people did not typically own or use them; Most people would primarily rely on walking. Void of high speed vehicles, Pauger had carriage and pedestrian use in mind when designing the grid.

The Desire streetcar rolling downriver approaching the corner of Bienville and Bourbon Streets. Note that motorist had to yield to the flow of traffic created by the streetcar line.

Before the advent of the individual use automobile, mass transit was introduced to the French Quarter. Famously immortalized by Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, the most famous route to operate in the Quarter was the Desire streetcar line. The route was introduced by the New Orleans & Light Company in 1920. The streetcar ran upriver on Royal Street to Canal, looped on Canal, and went downriver on Bourbon Street to Desire Street in the 9th Ward until 1948.

Today, city planning in the federally protected historical district exist to accommodate the private automobile. Streets have been widened to allow for vehicle traffic and parking, resulting in significantly reduced pedestrian space. Narrow sidewalks force pedestrians into constrained, often unsafe conditions.

The dominance of the motor vehicle in the French Quarter has morphed into outright villainy. The Quarter has become a race track for speeding, cars peeling out, hit and runs, people have been struck and drug under vehicles for miles, vehicles have been weaponized and used in acts of terror, drive by shootings, robberies, get away cars, road rage, the list goes on. During festivals and large events, the allowance of motor vehicle access within the Quarter exacerbates these issues, creating conflicts between vehicles and pedestrians in crowded spaces.

Over the past decade, I have devoted more than 20,000 hours to studying the intricate dynamics of the French Quarter’s streets. My work as a pedicab driver and bicycle tour guide has afforded me a unique perspective, enabling detailed observations of traffic patterns, infrastructure inefficiencies, and pedestrian behavior. Through this extensive, hands-on experience, I have identified systemic dysfunctions and developed potential strategies to enhance safety and functionality for all users—pedestrians, cyclists, carriages, and motorists alike.

Having worked in the Quarter year-round, at all hours, and during major events such as Mardi Gras, sporting events, and large scale festivals, I have acquired a comprehensive understanding of the district’s traffic management challenges. These experiences have informed my proposals for improving the Quarter’s transportation framework. One such concept involves significantly restricting public motor vehicle access within much of the French Quarter. Under this proposal, full motor vehicular access would be limited to residents, delivery services, sanitation, utilities, construction personnel, and first responders.

This approach seeks to prioritize pedestrian safety, reduce motor vehicle-related hazards, and restore a balance more in line with the original intent of the district’s historic design.

I. All Vehicle Access and Zoning

This concept divides the French Quarter into three zones, identified by the colors of the French flag: Blue, White, and Red. The perimeter streets—Canal Street, North Rampart Street, Esplanade Avenue, and Decatur Street/North Peters St.—would remain accessible to all vehicular traffic. Each of the three zones within the Quarter is designed to allow vehicles access to one riverbound street (Toulouse) and one lakebound street (Dumaine) for effective circulation.

Blue Zone: Bounded by Canal Street, North Rampart Street, Toulouse Street, and North Peters/Decatur Street.

White Zone: Bounded by Toulouse Street, Decatur Street, Dumaine Street, and North Rampart Street.

Red Zone: Bounded by Dumaine Street, Decatur/North Peters Street, Esplanade Avenue, and North Rampart Street.

II. Bicycle Lanes

To promote safety and traffic calming, designated bike lanes should be expanded and introduced along key thoroughfares:

Existing Infrastructure: A separated bike lane already exists on the downriver portion of North Peters.

Proposed Additions: Protected bike lanes can be installed on the upriver portion of North Peters and Canal Street, where street widths are sufficient. Painted bike lanes can be added on Decatur, Esplanade, Dumaine, and Toulouse Streets to encourage cycling and provide safe access for bicyclists.

North Rampart Traffic Calming: North Rampart is the Autobahn of the French Quarter. Speeding is beyond excessive and it goes unchecked. North Rampart can be reduced to one motor vehicle lane (riverbound) alongside the streetcar tracks. This modification will mitigate speeding and enhance pedestrian and cyclist safety. A separated bicycle lane can be added to encourage bicycling to and in the historic district.

This image is a potential mock-up of how the riverbound side of North Rampart in the French Quarter could look.

III. Additional Traffic Lights

While the existing traffic signal network supports efficient flow, the following additions are proposed for improved safety and traffic management:

Dumaine and North Rampart Street

Esplanade Avenue and North Peters Street

* Currently every corner of the three zones has a traffic light except for these two intersections. These intersections would need traffic lights for the proposal to work.

IV. Taxi and Ride-Share Stands

Dedicated hack stands should be designated along major access streets, such as Canal, Toulouse, Dumaine, and Esplanade. Strategic drop offs on Canal, Toulouse, Dumaine, and Esplanade will drop passengers 2 to 3 blocks away from their destinations. Priority should be given to city-regulated taxis with CPNCs, while ride-share services should have fewer designated zones.

V. Retractable Bollards

One of my most cherished inspirations is Vincent Van Gogh, whose vibrant strokes breathe life into the soul of history. Driven by a longing to walk in his footsteps, I journeyed to Arles, France, a town steeped in his legacy. Upon arriving at the train station, I was struck by a peculiar and enchanting silence—I scanned the surroundings, puzzled by the absence of taxis. The mystery soon revealed itself as I walked closer to the heart of the historic city center with luggage in tow.

Arles had embraced a bold and elegant solution: limiting motor vehicle access within its historic district. As I approached the ancient ramparts, I witnessed a fascinating system in action. A driver paused at an entry point, scanned an access pass, and with a quiet, mechanical grace, a bollard retracted into the ground, granting the vehicle passage. As soon as the car passed through, the bollard rose again, preserving the sanctity of the pedestrian haven.

The sidewalk entryways, beside the street with the retractable bollards, are graced with elegant metal gates and elevated concrete flower beds. These features, both practical and elegant, ensure no motor vehicle can trespass onto the sidewalks, safeguarding pedestrians and preserving the sanctity of their journey.

The streets of Arles were unlike anything I’d experienced, prioritizing people over motor vehicles. Wide pathways, with limited motor vehicle access, were a canvas for pedestrians to wander, cafés to sprawl their seating into the open air, and life to unfold at a human pace. It was a poetic reimagining of urban space, one that seemed to whisper Van Gogh's own love for the simple, tangible beauty of everyday moments.

A pedicab picking up passengers in Place de Forum, Arles.

Reflecting on this, I couldn’t help but draw comparisons to our own streets, which often sacrifice pedestrian comfort to accommodate the unyielding dominance of motor vehicles. The system in Arles, however, invites a thoughtful adaptation. Our streets may be wider, but with careful planning, retractable bollards could be positioned at the 24 entry points into the Blue, White, and Red Zones—two per entry point—to prevent drivers from squeezing through unauthorized spaces. Designed with inclusivity in mind, these bollards could also be spaced to allow access for pedicabs, embracing a balance between tradition and modern practicality.

Arles left me with a profound appreciation for how small changes can elevate the spirit of a place, transforming it into a haven for people to connect, reflect, and experience life with intentionality. Its thoughtful design is an enduring lesson in how history and modernity can harmoniously coexist.

VI. Access Pass System

An access pass system would regulate vehicular entry into the Blue,White, and Red Zones. The pass can be universal and give all permit holders full access to navigate the entirety of the French Quarter. The pass will have to be applied for and approved by the city. Permits would be issued to:

French Quarter Residents (with access to free long term street parking within the 3 zones). A parking permit will need to be placed on the rearview mirrors of all residential cars with access passes. This will help identify cars that may have illegally gained access to the 3 zones).

Delivery vehicles (including small business owners who deliver their own goods), sanitation vehicles, utility providers, and construction crews.

Hotel shuttle buses for guest transportation.

First responders and other essential city, state, and federal workers.

Mule Carriage Drivers

VII. Pedestrian Malls

To enhance walkability and reduce vehicular conflicts:

Bourbon Street: Extend pedestrian-only hours to 4:00 PM–6:00 AM and expand the pedestrian zone from Canal Street to St. Philip Street.

Royal Street: Broaden sidewalks and restrict parking from St. Philip to Bienville Streets. One shared lane for permitted motor vehicles with access passes, bicycles, scooters, mule and carriages, and pedicabs should be maintained with a 10 MPH speed limit and a shoulder broad enough for delivery vehicles to stop.

VIII. Rezoning Parking Lots

Existing parking garages within the French Quarter occupy spaces where historic buildings once stood. Zoning can repurpose these spaces for residential and commercial use. They could alternatively be leased to access-pass holders to reduce reliance on street parking.

* The images above are a then and now comparison of the 500 block of Rue Chartres before the parking garages were erected.

IX. Prioritizing Bicycles

The bicycle, humble yet profound, should be granted full access to the French Quarter, weaving through its storied streets with quiet grace—save for pedestrian sanctuaries like Jackson Square and Bourbon Street from dusk to dawn. In its simplicity lies a truth that echoes through the corridors of history: the bicycle is not merely a vehicle but a symbol of freedom, a gentle defiance of haste and excess.

Consider the Netherlands, a land that shares with New Orleans a geography shaped by water’s will. After Hurricane Katrina, we turned to the Dutch for wisdom on water management. Yet their lessons extend beyond the dikes and levees. The Dutch have shown the world how to reclaim urban life from the tyranny of the automobile, their cycling culture a testament to the power of thoughtful design and resolute vision.

Some skeptics dismiss the idea of robust bicycle infrastructure in New Orleans, clinging to misconceptions: “Their city planning would never work here,” they argue—yet the Netherlands and New Orleans share the same landscape. “The weather is too harsh,” some might claim—but anyone who has faced the biting winds or wintry tempests of the North Sea would scoff at such a notion.

The Dutch did not stumble upon a cycling utopia by chance. They built it, mile by mile, constructing a dense, 22,000-mile network of separated bike paths. They calmed their streets, taming the motor vehicle with over 75 percent of their urban streets having speed limits of 19 mph, that honor the rhythm of human life. They invest $35 per person annually in cycling infrastructure—a small price for the wealth of benefits reaped.

And the returns? They are as measurable as they are meaningful. Safer streets, with traffic fatalities drastically reduced—just 3.4 deaths per 100,000 people annually, compared to 10.6 in the United States. Streets where children play, where neighbors greet one another, where the air carries the scent of flowers, not exhaust. Streets that breathe life.

The bicycle offers what the automobile ads promise, but so often fails to deliver: freedom. Freedom to move with ease and intention, freedom from congestion, freedom to experience the world as it unfolds before you. It is not merely a mode of transport but a quiet revolution—a way forward, a return to a life lived at human scale.

Some practical ways this scale would look in the French Quarter would be to:

Allow bicycles full access to the French Quarter, excluding Jackson Square and Bourbon Street during pedestrian mall hours.

Expand bicycle parking corrals (like the one on St. Peter and Royal), ensuring sufficient access for private bikes while limiting further Blue Bike corral installations. The penalty for parking Blue Bikes outside of their designated corral in the French Quarter should be raised to $7.00.

X. Increase in Pedicabs

To accommodate reduced motor vehicle access, the cap on pedicab permits should be increased. Rates may be adjusted to reflect demand, providing an efficient and eco-friendly transportation option for New Orleanians and visitors.

Conclusion

This proposal represents a conceptual framework for improving the French Quarter’s and New Orleans overall quality of life. While implementation will require significant investment, the benefits—enhanced safety, reduced congestion, and preservation of the district’s historic character—are invaluable. As a city, we must prioritize sustainable, pedestrian-focused planning to ensure the French Quarter remains a vibrant and accessible space for New Orleanians, visitors, and future generations.

- Eric Gabourel